The Fotografiska New York exhibition features the works of artists like Mickalene Thomas, Kara Walker, Carrie Mae Weems, and more.

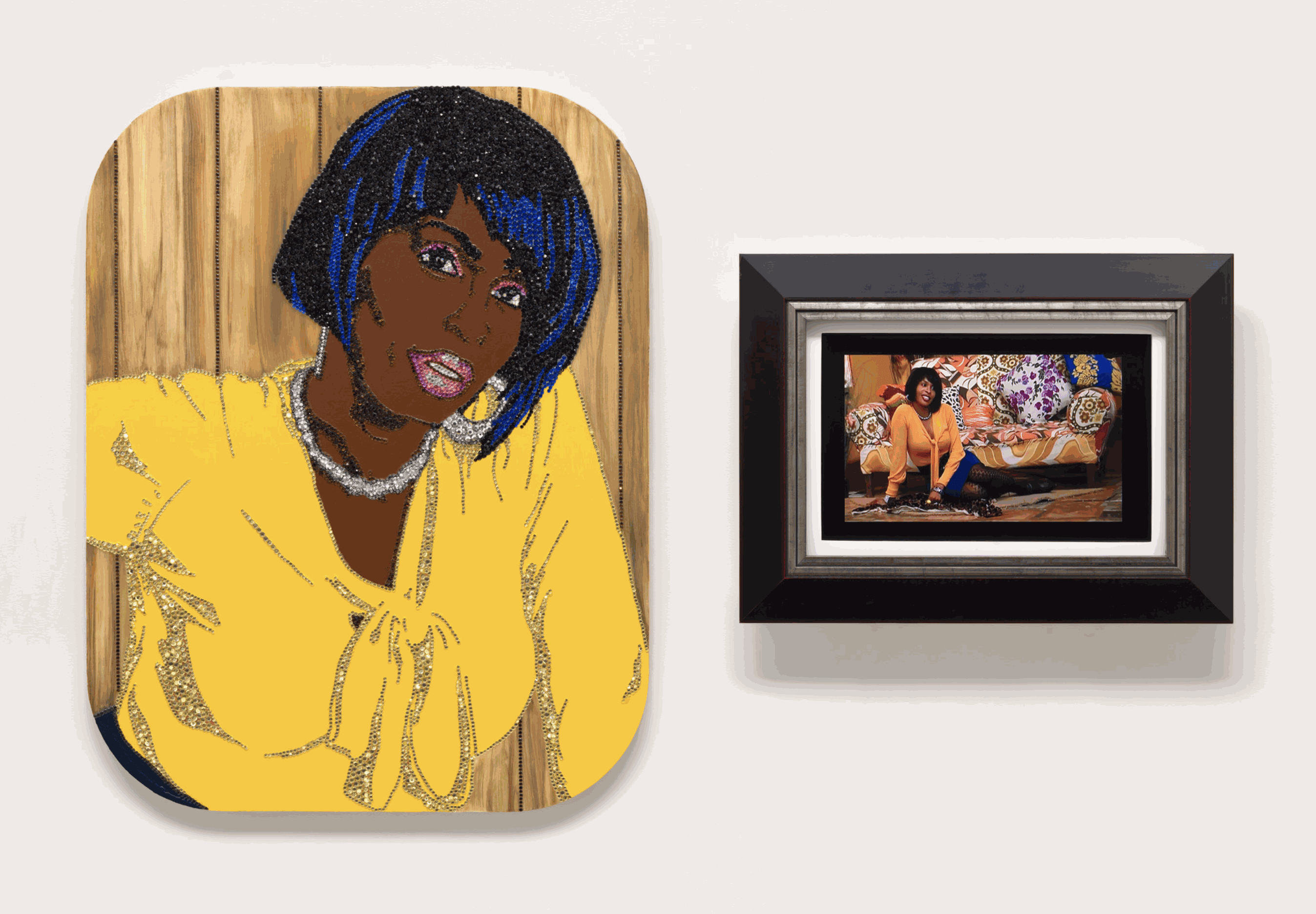

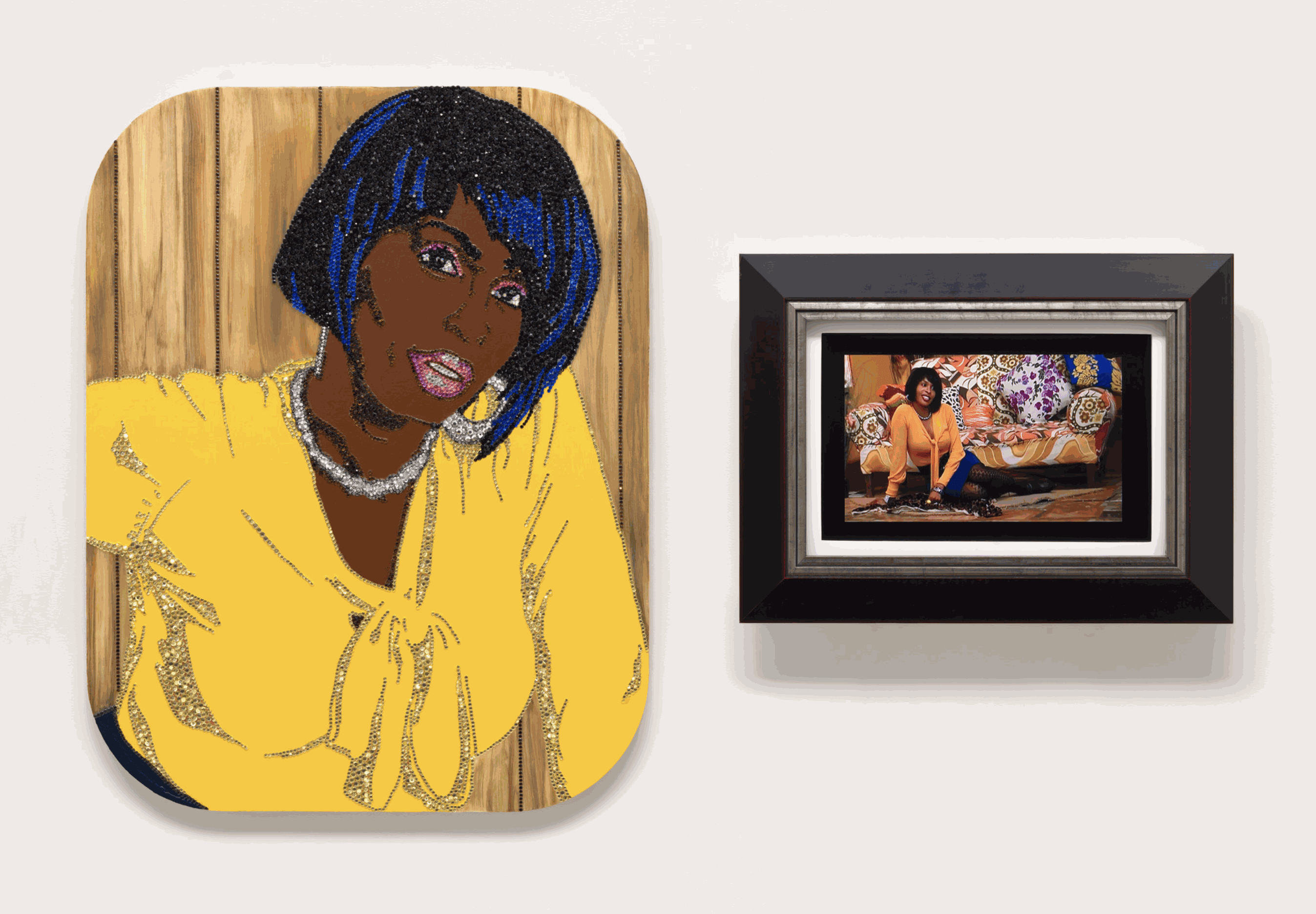

Mickalene Thomas, Ain’t I a Woman, 2009. Video (color, sound; 3:33 min.), and rhinestone, acrylic and enamel on panel. Dimensions: Panel: 36 x 28" (91.4 x 71.1 cm) Framed Monitor: 17 3/4 x 24 x 5 3/8 in.

Tracing the history of Black womanhood and investigating the many modes of representation we’ve existed in through visual culture is a task that requires vigilance, care, and inherent understanding, both from a present standpoint and retrospectively. “Black Venus,” a new exhibition at Fotografiska New York, demonstrates this beautifully through the works of several artists, all of whom illustrate the legacy of the Black woman with individual agency and talent.

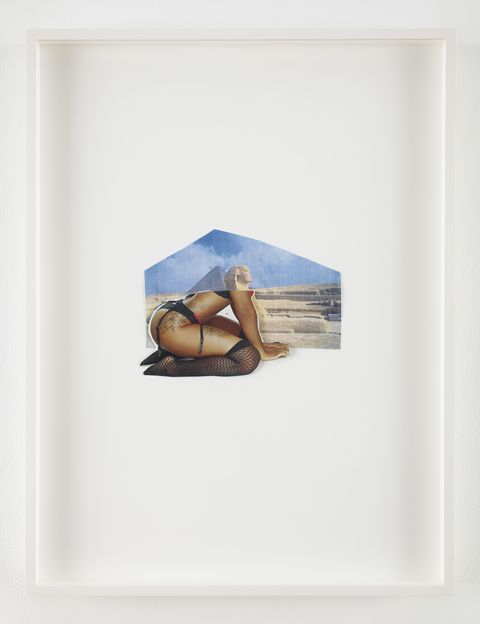

The exhibition, created by British Nigerian curator Aindrea Emelife, draws upon references from the past that have influenced toxic Western perception of the Black female body, such as colonial-era fetishizations and exoticisation.

“The idea for ‘Black Venus’ had been rumbling in my head for years, possibly decades, as my mother told me the story of the Hottentot Venus”—Sara Baartman, a South African woman who was exoticized and fetishized as a tourist attraction traveling around Europe—“aged around seven or eight,” Emelife says. “The show is in many ways an autobiography of all the Black women I’ve met and have yet to meet, as well as a love letter to a community that is so often told we’re ‘too much.’ I thought this was urgent.”

AMBER PINKERTON

The show features works by some of the most influential Black women in contemporary art, including Renee Cox, Coreen Simpson, Deana Lawson, Carrie Mae Weems, Mickalene Thomas, and Ming Smith. Cox’s reimagining of Baartman, titled Hot-en-Tot, is particularly powerful, as it reclaims ownership of the Black female body by covering areas that were exploited by the white male gaze in the original painting.

“The most compelling part about Hottentot was finding out her history and how she was shown as a freak on display throughout Europe. When she died, that wasn’t enough to stop the tomfoolery, as she was then dissected and presented in a vat of formaldehyde, also toured throughout Europe, until Nelson Mandela became president of South Africa and was able to reclaim her body parts from France to give her a proper burial,” Cox explains. “Knowing that history, and then finding myself, one day, in a Halloween costume store and seeing these big Black plastic breasts and buttocks, I knew at that moment that I had found the proper accouterments in producing my piece.”

Miss Thang—inspired by the “Black bougie housewife”—is another one of Cox’s contemporary artworks to be featured in the exhibition; it originates from a separate body of work she created during a self-proclaimed midlife crisis. “I felt I needed to create a visual representation of a Black middle-aged woman who was suffering from anxiety or clinical depression like Valley of the Dolls,” she says. “I wanted to do it in a visually dignified manner, because the images that populate the worlds of such things are usually of Black women looking very crusty and downtrodden.”

Miss Thang by Renee Cox.

Elsewhere, “Black Venus” celebrates the iconic performer Josephine Baker and challenges the sexualization of Black women through the modern work of Ming Smith, while photographer Coreen Simpson, whose career spans back to the late ’70s, presents a powerful masked nude series, centering a sense of control and ownership for its subjects.

“When I looked at nudes in the history of photography, I noticed that the greats never focused on the faces of their subjects. The body was the focus,” she explains. “I had a few masks from my travels and thought to place one on my model. I think masks add mystery to the subject, and as the great fashion designer Coco Chanel once said, ‘One replaces age with mystery.’ I say, every woman, at every age, should have a bit of mystery.”

"This is a love letter to a community that is so often told we’re ‘too much.'"

With each piece, “Black Venus” champions not only the mystery of Black women in all our forms, but the power, magic, and resilience we possess, just as much as it focuses on our softness and grace. “I want this exhibition to highlight the expanse that Black womanhood is. We cannot treat it as a monolith—this was key in the selection of artists, which range in generation, includes nonbinary voices, and has an international scope,” Emelife says.

She’s also trying to address a historical wrong. “I hope it also highlights the deliberate erasure of Black women in art history and history. Whilst walking through the show, many have expressed the necessity for shows like this, and the lack of them historically. I was deeply inspired by ‘Le Modèle Noir,’ the groundbreaking work Denise Murrell did for the Musee d’Orsay in Paris, with the radical renaming of the artworks featuring Black female sitters, which now reference their actual names. Thelma Golden’s iconic ‘Black Male’ exhibition shone a light on how Black masculinity is seen in America. I hope this show does something similar for the way Black women are seen in the world.”

Untitled (2014) by Kara Walker.

Miss Lesbian I (2009) by Zanele Muholi.

Agency is another key theme throughout the exhibition, and it sets the tone for the future of art, even more so with the rise of NFTs. “For the longest time, artists have not been truly in charge of the destiny of their art, the works are mostly in the hands of a few galleries and collectors,” Cox says. “With the advent of the block chain technology, artists are starting to be in a more powerful place by cutting out the middleman, and the industry will become much more transparent as a result.”

This sense of ownership over yourself is just as crucial in dismantling societal viewpoints and perceptions of Black women and the Black female body—a movement we’re seeing not only in the art world but through shapeshifting women in pop culture, among other fields.

“Having control over how we are viewed is vital. For so long, Black women have been trapped by convenient stereotypes and imaginations,” Emelife emphasizes. “This is why I focused on the Black woman, as captured by Black woman and nonbinary photographers and artists. I wanted to envision a space where Black women have control over the narrative and excavate history to reclaim it. If we think of the ’90s ‘music video vixens,’ for example, and the rise of artists like Megan Thee Stallion, Cardi B, and the City Girls, who now empower Black female sexuality, that was [once] only acceptable when commercialized as an accessory or when seen as an extreme. Once agency is reclaimed, potential can be realized.”

Tickets for “Black Venus” at Fotografiska New York are available for purchase here.